A Wealth Tax Would Be A Logistical Nightmare

Recently, I’ve been spending a bit too much time on Quora answering tax questions. It’s surprisingly fun, like a Social Network that I actually enjoy. But then, every now and then I get stuck on one of those “big theoretical questions.” Like today, where I made the mistake to responding to a wealth tax question.

After apparently writing a dissertation in response, I decided I’d post a modified version over here. There have been all kinds of calls for a wealth tax lately, so I figured I’d put my two cents out there on the practicality of it all.

A Background on the Wealth Tax

There’s nothing quite like wealth and taxes to get people’s blood boiling. We see these super wealthy individuals flying to space and buying ridiculous yachts, and it can inflame that seed of jealousy in even the most carefree individuals.

Then, when ProPublica released it’s report into how much taxes some of these super wealthy people paid compared to how much they owned, the internet exploded.

After calming down, it became pretty obvious why these individuals didn’t pay more in income tax: they didn’t have INCOME. They were wealthy, but that wealth was mostly in their companies.

Which led to the next question: why don’t we tax their wealth?

Back to Quora

Today, I was asked why we don’t implement a wealth tax when there are hundreds of rich people and corporations that pay zero income taxes.

The zero income tax statement is a whole discussion to itself, but I decided to skip that part and focus on the first part.

Why don’t we have a wealth tax?

There’s three very clear reasons why Congress hasn’t implemented a wealth tax: (1) it may not be legal, (2) it would be a logistical nightmare, and (3) it’s unclear if it would be a net economic benefit.

Legal Concerns

First, the legal issue. Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution gives Congress taxing power, but it has limitations. Specifically, it has proportion limitations:

No Capitation, or other direct, Tax shall be laid, unless in Proportion to the Census or enumeration herein before directed to be taken.

Article 1, Section 9

This limitation turned into a serious issue when Congress first introduced an income tax. The Supreme Court ruled in 1896 that the income tax would only work if the tax was apportioned based on state.

This means California would have to pay the same amount proportionally based on its population as Mississippi. Even though Californian are wealthier per capita.

Continuing that issue on, Californians would have to pay a relatively lower tax rate than Mississippians. What rate would the Feds give the individuals in each state? There was no way to know until the taxes were paid.

Which was obviously a virtually impossible problem to solve. Especially in the pre-super computer days.

As a solution, Congress passed the 16th Amendment. Let’s take a quick look:

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.

Amendment XVI

See the problem? The amendment gets around the Constitution…but ONLY with INCOME taxes.

Unless we massively change our definition of income, wealth is NOT income. The 16th Amendment wouldn’t apply, pushing Congress back to our Article 1, Section 9 proportionality problem.

So we can tax Jeff Bezos’ wealth in Washington and Elon Musk’s in wherever he’s living these days…but only in proportion to the super wealthy people we tax Alabama.

Huh, turns out it’s NOT Nick Saban, as I originally thought. It’s the heirs of a $4 billion dollar fortune. Which sounds like it’ll be a HUGE limitation on that nearly $200 billion that we want to tax from Jeff Bezos.

Logistical Nightmare

Let’s assume Congress were able to pass this wealth tax. Okay…now how would the IRS enforce it?

This is not a small issue. The tax code has been specifically set up to primarily tax people on actual transactions with verifiable numbers based on what a third party actually paid for it. This is different from your typical GAAP financial accounting that corporations use, or government accounting, both of which rely heavily on estimates.

Congress really doesn’t want the IRS going in and making guesses. Not only does that take a lot of time and resources, it will lead to lawsuits from people who disagree with the estimate. Rich people with expensive lawyers.

Logistic Issue #1: Economic Income/Loss, Not Realized

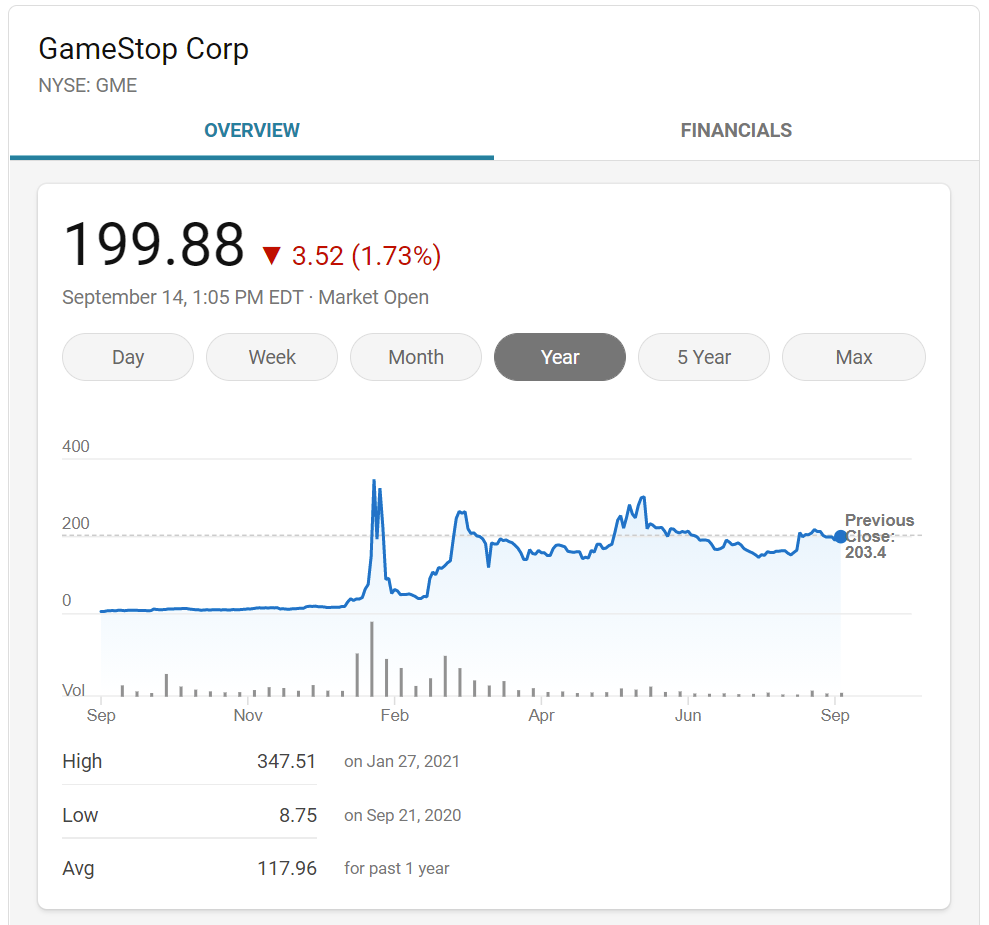

Let me put numbers to this. Let’s say Jeff Notbezos buys 2,654 shares of Gamestop stock for $50,000 on December 31, 2020. As of that moment, his wealth hasn’t changed, he’s just moved it from cash to stock. So there’s nothing to tax.

But now Gamestop is looking absolutely crazy. Let’s assume it closes at $200 a share on December 31, 2021. He now has wealth of $530,800. An economic gain of $480,800.

So far, this is easy enough to figure out. It’s exactly what ProPublica did in their reporting.

But what if, on December 31, 2022, GameStop ceases to exist. His shares are now worth $0. Do we allow Jeff to then take a $530,800 loss? I think we’d have to. We allow realized capital losses (to the extent a person has capital gains), it seems like we’d have to do the same with these theoretical losses.

After adding in this new wealth tax, the headlines would be the same: “Jeff Notbezos pays $0 in taxes.” It’s not until you get to paragraph 3 that it’s revealed it’s because his wealth decreased.

Logistical Issue #2: Tracking Basis

Each year, you’d have to reevaluate your basis in the company. It’d be annoying, but a fairly minor issue compared to the other problems. At least if you have a publicly traded company (more on that in a minute).

Logistical Issue #3: Where’s the money?

In general, the IRS doesn’t tax things where there isn’t money to pay for it (yes, I know there are exceptions, but they are rare).

If we go back to our Jeff example, this person now has to pay for taxes on $480,800 of income where he didn’t actually get any money. If Jeff’s only wealth is in the company, are we going to make him sell the company to pay for taxes?

This is could be a potentially HUGE issue. What if a person owns 100% of a company instead of a small piece. If all of their wealth is in this company, are we really going to make them give up part of their control in their company just to pay for taxes? Especially since the company value would be completely based on an estimate (the taxpayer hasn’t sold any stock yet, so the IRS can’t know what people would actually pay for it).

This isn’t a hypothetical, either. We’ve had many tech companies that were cash poor from losing money year after year after year but valued at billions of dollars. Their owners would literally have to either sell their company or hope a bank would lend them money just to pay taxes on a THEORETICAL gain.

Which brings us to the biggest issue of all.

Logistical Issue #4: What If The Wealth Isn’t Not Publicly Traded

When we talk about these super wealthy individuals, we always talk about a handful in the public eye: Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, etc. What do they typically all have in common?

Their wealth is primarily in publicly traded companies.

It’s pretty easy to figure out the value of a publicly traded company.

What about non-publicly traded companies? Or what if they own a lot of land? How about patents of their own creation, how would that be valued? Or any one of a million other things where the value isn’t known until it’s actually sold.

(Serious question: would a Banksy pay a wealth tax if he holds onto his own art?)

This is what the IRS wants to desperately stay out of. They don’t want to try to figure out what everything is worth year after year after year. And, honestly, I’m not sure we could hire and train enough assessors to even make that kind of estimate feasible.

Just think about how mad people get when their property tax assessments come back. And those numbers are based on the sale of similar homes.

Imagine the lawsuits that will fly when the IRS tries to claim that the one-of-a-kind artwork Bezos purchased from an up and coming artist is now worth 10x what he bought for it.

And before you say “let’s just tax publicly traded companies”, consider how much incentive that would give to never make companies public.

The more you tax something, the less you get of it.

Which brings me to my last point.

What Is Our Goal?

What is the point of our tax system?

It’s not an easy question, and people will have different answers. But, ultimately, a tax system has to raise money.

Taxing wealth is going to have economic consequences. How will these super wealthy individuals rearraign their lives to plan for the tax? Will we actually bring in more revenue, or will all the best ideas flee to Switzerland and Ireland, so we lose out on both the innovation AND the tax revenue?

The fact is that we don’t know.

It sounds nice to stick it to the rich. It sounds nice to make them “pay their fair share” But if we’re not careful, we could end up, to use the old idiom, cutting off our nose to spite our face.

We need to be extremely careful about sending shocks like this through our economy. We need to get past the stage one thinking of “I want these people to pay” (literally, in this case) and consider the likelihood of negative consequences.

None of this is to say that we CAN’T do a wealth tax. We just need to be very careful about what we do, rather than emotionally push through a poorly thought out law because we think a handful of people aren’t paying enough taxes.

The last time we tried to “stick it to the rich” we ended up with the Alternative Minimum Tax. It was a disaster that took nearly 40 years to (mostly) get off the books. A wealth tax could potentially be so much worse.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed the article, you’ll likely enjoy subscribing to my newsletter. It’s not always quite so tax legislation heavy, but it does have tax talks mixed in my the entrepreneurial excitement. Plus there’s dog stuff.

Image by Hans Braxmeier from Pixabay